Wondrous strange

Some thoughts on Hamnet. Yes, I’m here to spoil your fun!

Don’t worry, I’m not actually here to spoil your fun. No entirely. If you’ve been enjoying the book or film of Hamnet, that’s all right with me. I’m happy when anyone takes pleasure in art. I’m even happier when they pay a bit of money to do so and help fund future creations. Plus, anything featuring Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley can’t be entirely bad.

Also - importantly - I haven’t seen this new film and so I am in no position to judge it.

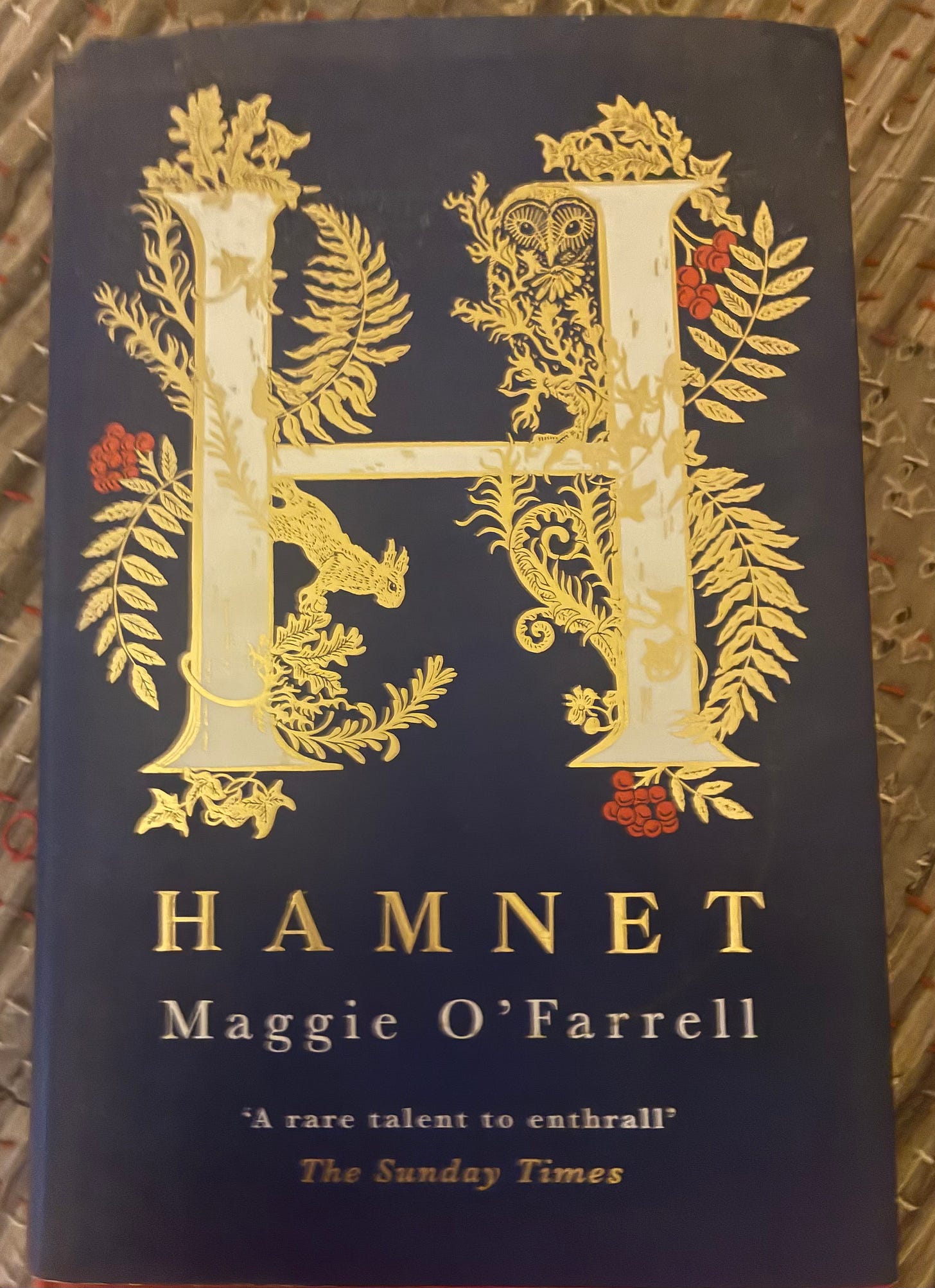

But then again, the reason I haven’t seen the film is that I didn’t much like Maggie O’Farrell’s source novel. Its popularity with critics has been bugging me ever since it was up for the Guardian’s Not The Booker Prize in 2020 and it fell to me to review it.

Here’s what I wrote back then:

It takes a brave writer to try to put words in William Shakespeare’s mouth. Or foolish. In Hamnet, Maggie O’Farell almost gets away with it - and also almost manages to tell a story that feels both new and convincing.

The Hamnet of the title was Shakespeare’s son. He died aged just 11 in 1596. Although the cause of this death has always been a mystery, plenty of scholars have suggested that he succumbed to bubonic plague. O’Farrell goes to town on this theory, indulging in a long digressive chapter detailing the origins of the fleas in Alexandria and series of events that are needed for, as she puts it with a lamentable lack of subtlety, “a tragedy to be set in motion halfway across the world.” In this retelling, Hamnet became the inspiration for the play Hamlet, four years later.

To maintain this story’s credibility O Farrell mainly keeps Shakespeare offstage. We feel him most as an absence, away in London while most of the action takes place in Stratford - and because we don’t see him producing his immortal verse, we are more able to imagine him doing so. Even when Shakespeare is on the scene, O’Farrell gives him few lines. She prefers to portray his speech indirectly and have him “gesturing, clutching his hair, his voice still churning away, throwing out words and words and more words into the greenery.” When he does speak, she generally keeps his utterances simple and straightforward. Although there are unfortunate lapses. At one point he can’t find his wife Agnes and cries: “The fates have intervened and swept her away from me, as if on a tide, and I have no idea how to find her.” At another he complains that his grief is “like a wheel ceaselessly turning at the back of my mind.” Of course, it’s quite possible that such banalities came out of the mouth of the Bard, but when they’re set down on the page it’s hard not to draw invidious comparisons with his real poetry.

No matter. For once, Shakespeare isn’t the main draw. Agnes, his wife, is this novel’s star and treads the boards with style. In many accounts of Shakespeare’s life, this Agnes (more famously called Anne Hathaway) is portrayed as an illiterate stay-at-home whom Shakespeare abandoned for a more interesting life in London. O’Farrell has reclaimed her as someone who has her own brand of intelligence and independent life. She has an extensive knowledge of herbs and horticulture that makes her one of the first resorts of the sick and infirm in Stratford, and there are fine descriptions of this mysterious wisdom and her “witch garden”, where there are “rows of herbs, flowers, plants, stems that wind up supporting twigs” and where “Agnes can be seen, most weeks, moving up and down the rows of these plants, pulling up weeds, laying her hands on the coil of her hives, pruning stems here and there, secreting certain blooms, leaves, pods, petals, seeds in a leather bag in at her hip.”

Agnes and her world feel real and bright, most of the time. But you do have to accept a certain amount of mumbo-jumbo about her “foresight” and her ability to tell things about people by holding their hands in a special way. When she does this to Eliza, her sister-in law, we are told, it is “the oddest sensation, as if something is being drawn from her, like a splinter in the skin or infection from a wound, at the same time as something else is being poured into her.” Worse, we are expected to believe that Agnes finds out about the death of Eliza’s sister through this magic hand-holding.

It would be just about possible to forgive such nonsense as a reflection on the more superstitious world of the 16thcentury, if there weren’t also an uncomfortable feeling that this book reflects more of our own concerns and morality than those of the Elizabethans. Would anyone then care, for instance, about the fate of farm animals and think “of the private cruelty behind something as beautiful and perfect as a glove.” Again, it’s not impossible - but O’Farell didn’t convince me.

There’s less to quibble about in her portrayal of grief and pain. The death of a child may be the easiest emotional target in fiction (give or take the loss of a much-loved dog), but that’s not to detract from the raw urgency of what happens in Hamnet.

O’Farrell makes us share Agnes’ terror when she sees buboes on her daughter: “They occupy such a potent place in everyone’s fears that she cannot quite believe she is actually seeing them, that they are not some figment or spectre summoned by her imagination.”

She makes us know the worst of all fears when the illness has Hamnet in its grasp: “It has wreathed and tightened its tendrils about her son, and it is refusing to surrender him. It has a musky, dank, salty, smell. It has come to them, Agnes thinks, from a long way off, from a place of rot and wet and confinement. It has cut a swingeing path for itself through humans and beasts and insects alike; it feeds on pain and unhappiness and grief. It is insatiable, unstoppable, the worst, blackest kind of evil.”

O’Farrell describes these agonies with such power that Hamnet would resonate at any time. Here in 2020, it’s easy to understand why it has moved so many people, in spite of its many flaws.

Curiously, that review is rather different to the one that finally was published in The Guardian.

Most of my criticisms disappeared somewhere in the process.

Was there a Big-Farrell conspiracy at The Graun? Was I subbed by Bowdler?

Before crying foul I should admit that I can’t remember how the review came to be softened up so much. It was published at the end of the first Covid summer, in September 2020, when things were weird.

Including, most probably, me.

Maybe I even made some last minute alterations when I was filing? Maybe?

Anyway, it doesn’t matter that much because the even more curious thing is that few of the problems that have continued to most annoy me about the book are mentioned in either version of my review.

Namely:

The entire conceit that there had to be a version of Hamlet in the world for Shakespeare to be able to write his play. As if he couldn’t just use his imagination and creative powers. (Because obviously, they weren’t good enough were they…)

The fact that Shakespeare has to have a magic wife. As if a real woman somehow isn’t enough for him. As if he couldn’t otherwise be entranced and in awe of a female of the species.

The fact that this wife was apparently more into 21st century New Age guff than actual Elizabethan Christianity and modes of thinking.

The horrible, mawkish, manipulative and, crucially, entirely unbelievable ending where - spoiler - the twins swap fates, thanks to more reasons of magic and nonsense.

And then there’s the broader cultural issue:

The fact that Hamnet has succeeded because it’s managed to land on just the right side of mediocre.

It isn’t terrible or strange enough to hate. But nor is it good enough to be interesting or challenging. It’s mostly harmless. Which is maybe another way of saying that it’s mostly useless.

Okay.

Enough.

Maybe I was here to spoil your fun. Sorry about that.

Meanwhile…

Telenovela by Gonzalo C Garcia has been getting some wonderful reviews. This one just came out in The Irish Times: “Telenovela is a convincing portrait of the darkest period in Chile’s modern history, which, by homing in on those on the wrong side of history, reflects the subtle weaponry of silence and language.” Sounds good to me.

I also loved this review - and reading from the book - here on Substack.

There’s plenty more discussion of the film of Hamnet, as well as much more positive book recommendations on my Links, Tips and Suggestions blog. Your ideas are also most welcome.

I just don’t think the play Hamlet is, in any way shape or form, about the grief of losing a child. That’s just…not the play’s concern. As an origin story for one of the most famous plays of all time, it simply doesn’t work.

I thought the film was more enjoyable than the book, but that may partly have been because it was filmed near to where I live. I admire Maggie O'Farrell's success and enjoyed I am, I am, I am, but it was a relief to hear someone whose views I respect who didn't enjoy Hamnet as my dislike of it met with incredulity among my writing group and other friends. Apart from the witchy stuff and the violent father which both felt heavy handed, my particular gripe is O'Farrell's obsession with writing adjectives and adverbs in clusters of three. In the passage you quoted she talks of a 'musky, dank, salty, smell' and once you notice that tendency its impossible to unsee it in every paragraph.